Cycles that Spiral

The Earth’s processes tend towards cycles that spiral. —Earthen Ethic No. 1

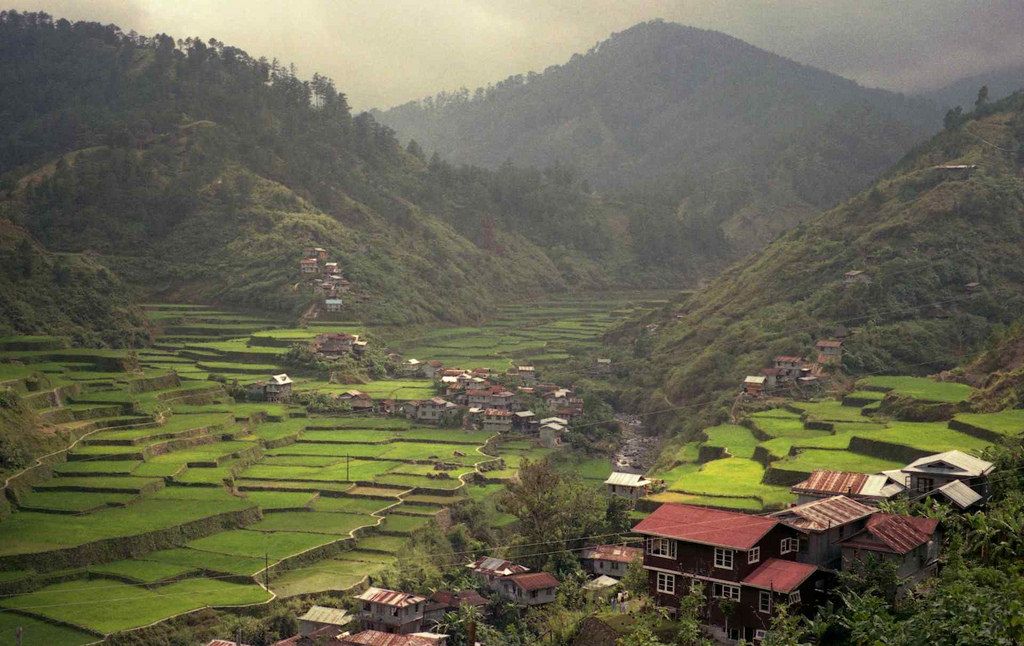

THE RUGGED GREEN MOUNTAINS OF NORTHERN LUZON have been the home of the Igorot people for untold generations. Each season, with the arrival of the migratory kilin bird, the planting of rice begins. Then, once the crop has turned gold and the kilin have flown on to the forest — the harvest. And then… always a little more. For after the rice has been taken home to dry, it is time for a ritual as old as the harvest itself. One by one, rocks are gathered up from the river to shore up the sides of the field. Stone by stone, the paddy is improved to better capture and disperse the flow of rain down the hillside. Season by season, the garden is enriched— becoming not just a better home for rice, but a better common home for crabs, frogs, snails, mud fish and more. With each season the Igorot’s management of soil and sun ever improved the vibrancy of the ecosystem. While not all harvests were as plentiful as the one before, over the generations the soil increased in fertility and the bounty never ceased. Igorot society thrived. Rivers remained clean and clear. The forests were respected and the kilin would always return. And then the next cycle would spin — always a little greener than before1.

Today as we seek to green our modern ways, we have much to learn from the way the Igorots managed their energy and matter. At the heart of their ancient kincentric culture contains an ancient ecological ethos that can help us make sense of the latest breakthroughs in thermodynamic theory and planetary science. As we shall see, both the ways of the Earth and the Igorots share a geometric resonance. Both tend their processes towards cycles that spiral and enrich. This vortical pattern underlies not only of how the Igorots steadily enriched their ecosystem— but also the way the Earth greened our once barren planet. This first aspect of the Earth’s cosmological character, can show us the geometric shortcomings of our modern linear and circular processes — and point us towards the green way forward.

However, to begin, we must return to the origins of our solar system.

As we saw in the Earth’s Stellar Story, the planets of the early solar system formed over 5 billion years ago. As each planet coalesced out of drifting stellar debris, it gained a kinetic pattern of energy and matter all its own. To this very moment, each planet’s unique combination of elements, chemistry, orbit, moons, magnetosphere and more continues to unfold. Much as a culture defines and guides all aspects of the life of its people, this cosmological character permeates all a planet’s processes. In particular those that repeat: its cycles — tending them in patterns that are unique to each planet.

In this way, our solar neighborhood has come to be. As Venus, Mars, Earth and all the other planets, spun around the Sun, they absorbed and adapted to a never ending torrent of solar energy. Like rain pouring down a hillside into streams, rivers and rapids, the sun’s energy shone down upon each planet’s surface spilling into planetary cycles — atmospheric flows, ocean currents, tectonic shifts. As the planet’s matter (soil, liquids, gases) was spun, the resulting cycles were driven by the rigid dictates of thermodynamics. In ways unique to each planet’s, the sun’s ever arriving energy was dissipated.2

Over the eons, the cycles on each planet unfolded and the character of each was expressed.

On Earth, one entropic adaption after another began to accumulate. Just as the Igorots would shore up their terrace walls with new stones every season, each Earthen cycle tended infinitesimally towards an ever improved configuration of matter to capture energy— adding an atom here, a chemical bond there. Like rice terraces capturing, fracturing and spreading out the rain’s downward flow, the Earth’s cycles did the same. As one cycle fractured into a thousand, and that into a million more, life began to unfold. Steadily, life-cycles adapted their spin towards ever more concentrated configurations of matter and ever better dissipations of energy.3

And, the Earth greened.

While, today’s contemporary physicists and philosophers struggle to articulate the connection of life’s emergence with thermodynamic dissipation4, the Igorots have a single, precise term– and with it, an ecological ethos that governs their cycle-centric culture.

All aspects of Igorot life and culture are guided by the virtue of ayyew. Men, women, households and communities are admired and respected to the degree in which they embody the principle. Ayyew means to not just just to be in sync with a cycle, but to tend to its spin.

Children first learn the concept of ayyew at meal time. It is ayyew to finish every grain of rice on one’s plate. Not because it is a waste — rather, because it is a cycle’s crescendo. The last grain represents the culmination of one cycle and the beginning of the next — and an opportunity for a little more. As one cycle ends and another begins, there lies the chance to grow strong so that one can contribute to it: to sow the next seedling, to help with the next harvest, to add a stone to the garden’s wall.

When there are leftovers from a process (burned rice, banana peels, grass cuttings, etc.) ayyew guides their transition to a subsequent cycle. Rather than simply compost the organic matter, it is more respectable, more ayyew, to feed them to the neighborhood pigs. While both methods lead to fertilizer, the resulting manure is far more concentrated in carbon and microorganisms, making it more effective at spreading over fields and gardens to disperse its nutrients out to the ecosystem at large.

Finally, ayyew guides the Igorot’s relations with the land. While the destruction of the forest is despised (how can one achieve any richer system of cycling?) the long labor of transitioning a grassy slope to a bio-diverse and fertile ecosystem is admired above all. Rather than the rush of rain down the hillside, instead it is caught in a fractal of zigs and zags. This way the downward flow of the hydrologic cycle (rain-river-evaporation-and-rain-again) is dispersed outwards and ever more equitably throughout the hillside ecosystem. Each terrace is thus enriched— but ‘riches’ not just in yield. Most especially riches of the planetary kind: ecological stability, resiliency, diversity, vitality and abundance — the very same characteristics that the Earth brought to our once barren planet.

Within the deep resonance of the Ayyew ethos and the Earth’s cosmological character, lies our first Earth ethic.

As we strive to ensure that our human enterprises are green, the Earth shows us the way forward. Just as the Earth tended its processes towards cycles that enrich, so too are we called to intend our own. When our human processes result in cycles that spiral their matter and energy in the same ways as the Earth, then they enrich in the same way. Such acts and enterprises can then be considered ecological contributions — and green.

Today, we are realizing that our modern processes all too often result in the opposite: greying, ecological depletion. Perhaps, no where is this better observed than in our use of plastic.

In an Igorot community the carbon molecules of a grain rice can be cycled from garden, to human, to pig, and back to the garden again indefinitely. However, although plastic is largely made of carbon, its molecules all too often have a one way destination. ‘Single-use’ and ‘disposable’ plastics entirely lack a plan for their circulation. Such linear products and processes are defined by linear goals: incineration, dumping, combustion, etc. In so far as these processes fail to plan for their subsequent cycle, they fail to embody the cyclical ways of the Earth.

To discern the color of our modern processes we must thus first ask about its end: is there an intention for subsequent cycles once the first is complete? Only when our processes have a plan for their next use, and the subsequent ones after that, can they begin to be considered ecological contributions.

So what then of our circular processes— are they sufficient to be green?

Today, many products are engineered to be circular — their next life is planned. In this way, PET bottles, carpets and casings are often designed so that when their first use comes to an end they can be recycled into something new. The materials of these products are considered indefinitely reusable ‘technical nutrients’5. In this way, modern processes strive to transition to a ‘circular economy’.

Insofar as such processes contain a plan for the next life of the product, they are an important step towards following the Earth’s circular ways.

However, circularity is in and of itself is insufficient.

After all, over the eons our neighboring planets spun in perfect circles about the sun— yet they did not green. No matter how much solar energy arrived, Venusian cycles did fracture and cascade. No matter how sustained Mercury's spin, its matter did not spiral into ever more concentrated and complex configurations. No matter how perfect their planetary circles, the ecological enrichment that we so long to replicate failed to take hold.

As we have seen in the ways of the Earth and the Igorot is, ecological enrichment requires a tended shift— always something more. Another stone added to the terrace wall. Another atom of carbon added to a protein molecule. While it may be an infinitesimal addition in itself, over an indefinite series of cycles the result is, quite literally, a world of difference. Indeed, it is the difference between between depletion and enrichment, grey and green.

As such, a plastic bottle may be indefinitely reusable, an economy circular, a company sustainable — yet like the surfaces of Venus and Mars, result in desolation.

For indeed, in the unfolding cyclical systems of the biosphere, there are no perfect circles — only cycles that spiral outwards or inwards, enriching or depleting.

As we strive to ensure our enterprises are green, not only must we plan for the subsequent cycles of our material and energetic processes, we must ensure that each iteration enriches.

The requisite spiral geometry clear, we can now delve deeper into the vortical character of enrichment itself. In particular, the outwards spin of energy and the inwards spin of our matter— our next two Earthen ethics.

With their help, we can further follow the example of the Earth and the Igorots.

NEXT: Chapter 8 | The Salmon's Spiral

PREVIOUS: Chapter 6 | The Ways of the Earth

WHAT IS THE TRACTATUS AYYEW? The Story

A decade ago, Banayan Angway and Russell Maier; an Igorot wisdom keeper and a western philosopher, joined forces to protect the Chico River in the remote Northern Philippines from an inundation of plastic pollution. Ever since, they have continued to explore the pressing modern relevance of indigenous ecological wisdom. Guided by the Igorot Ayyew eco-ethos, they are publishing a systematic theory of green and grey in the form of a philosophical treatise. The Full Story of the Tractatus Ayyew

Footnotes

1 For an account of the Igorots remarkable ecological synchrony see: William Henry Scott, (1959) Some Calendars of Northern Luzon, American Anthropologist 60(3):563 - 570

2 Entropy research by theoretical physicists posit a pattern of adaptive dissipation in the way matter organizes itself in the presence of sustained energy inputs. Meanwhile, parallel breakthroughs in cosmological epistemology help make sense of the Earth’s unfolding kinetic character.

3“The earth is more like an eddy in a river through which flows of matter continuously stream. It is replenished and depleted in a vortical cosmic dance." — Thomas Nail, (2021) A Theory of the Earth

4 Jeremy L. England et al. (2015), Dissipative adaptation in driven self-assembly, Nature Nanotechnology

5 The term ‘technical nutrient’ was first proposed by William McDonough. See: William McDonough, Michael Braungart (2002), Cradle to Cradle - Remaking the Way We Make Things, North Point Press.