The Problem of the Year

A Kincentric Critique of the Modern Year

A Kincentric Critique of the Modern Year

Like water to a fish, we're swimming in our modern notions of time. As minutes, days, weeks and months go by, we take these notions of time for granted, barely considering the impact that these concepts have. Perhaps most invisible and assumed of all is our modern concept of a year.

So deeply is this notion embedded in modern consciousness that to question it can feel naïve, even absurd. As one year gives way to the next, we collectively anticipate another precisely measured circuit of Earth around the sun: 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and change. This number has become so authoritative that few pause to ask wha¹t, exactly, it represents—or, omits. This year, we have come to believe, is a fixed quantity of time. A unit. A measure. A container into which life is neatly poured.

Yet this has not always been so.

And more importantly, despite our insistence– it is not so.

Our modern definition of the year rests upon a profound ontological error: not of arithmetic, but of emphasis. It mistakes measurement for meaning. It privileges precision over participation. And in doing so, it severs our lives from the beating, rhythmic cycles that truly make and mould the universe

A year is meant to represent our planet's spin around the sun. However, to understand the problem with the modern notion, we must first recognize that a simplified³ solar spin involves two distinct cycles:

- The rotation of Earth on its axis

- The orbit of Earth around the sun

The first cycle gives rise to the most immediate and visceral rhythm known to life on this planet: day and night. Almost all Earthly beings, human and otherwise, entrain themselves to this oscillation.

The second cycle—the solar orbit—is the one we call a year. When we attempt to measure it in days, its duration is not a clean and obedient number. Earth completes this journey in approximately 365.241299 days³.

Close enough to 365¼ to tempt simplification.

But not close enough to obey it.

It is this remainder—this fractional refusal—that has haunted calendar-makers for millennia.

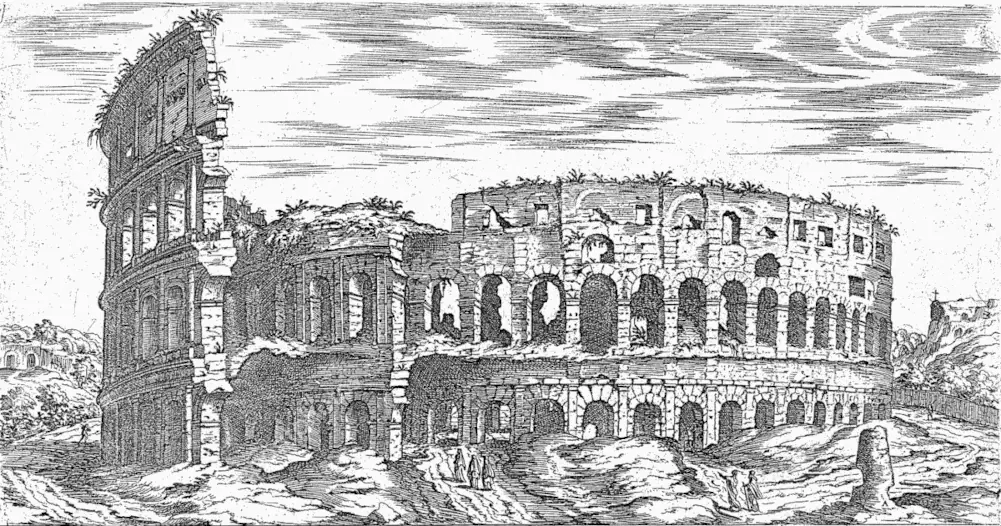

Ancient civilizations recognized the discrepancy and responded in different ways. As we saw in my previous essay, the ancient Egyptians added an extra day to their calendar every 4 years. Then, two thousand years ago, Julius Ceasar, borrowed this concept and refined it further so that the Roman calendar could be even more accurate. Then, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII “improved” the Roman system, by adopting the rule that there would be no extra day on centuries—00 years—except on those that are multiples of four.

While we call our calendar the Gregorian calendar, in effect the Roman one– the minor additions by Pope Gregory, and in the last century by governments, are simply refinements.

Each reform promised greater accuracy. Each moved closer to a perfectly regulated year.

Yet with each refinement, something essential was lost.

For all its technical ingenuity, the Roman calendar—and its Gregorian descendant—did not resolve the discrepancy between Earth's spin and orbital cycles. It concealed it. By burying two different cycles beneath layers of correction, the calendar transformed time into a linear mechanism. The year became a number that always fit, regardless of what Earth was actually doing.

In doing so, modern civilization gained an extraordinarily efficient tool for empire, administration, and commerce.

But it lost time itself.

For time is not linear. And cycles are not reducible without remainder. Above all else time is cyclical, and in so far as these cycles interweave: synchronistic.

“If you want to find the secrets of the universe, think in terms of energy, frequency, and vibration.” – Nikola Tesla

Kincentric cultures—ancient and ongoing—understood this intuitively. For them, what we call a “year” was not an abstract duration, but a lived recurrence. Their temporal units were Earthen rhythms, not numerical intervals.

Each year, the return of the kilin bird marked the time of harvest for the Igorots of Northern Luzon². In the land of the Wet'su'weten in North Pacific coast of America, the rivers would boil each Autumn with salmon, summoning the community into shared labor, feast, and story. It was a yearly, cyclical moment that happened to coincide with a particular point of Earth's orbit of the sun– but for whom the cycle was far more important than the precisely calculated date and time.

Their yearly celebrations were not on time, but in rhythm.

Crucially, these cultures were not imprecise in their measurement of time. Many achieved astonishing astronomical accuracy. Stone alignments such as those at solstitial sites attest to a refined understanding of Earth’s movements. Yet precision was always subordinate to to the cycle itself. Measurement served the cycle; the cycle did not serve the measure.

This is the beating heart of the matter.

Beginning with Roman reform, metrical quantification came to dominate the cycle itself. Intercalary time—those living margins where cycles failed to align—was abolished in favor of self-correcting mechanisms. Fractions replaced festivals. Corrections replaced consciousness.

Over centuries, this logic compounded.

The result is the calendar years we now inhabit: a grid of arbitrary and misnamed months (October is from the Latin root for eight, yet it is the 10th month!). It is a temporal architecture optimized for economic administration over ecological integration (The word calendar comes from the Latin for account book). And its beginning and end are fundamental ungrounded: December 31st marks no harvest, no solstice, no Earthen or planetary occurrence—only the exhaustion of a number.

Despite its digital polish and global synchronization, this system is profoundly disconnected from Earth’s raw rhythms. It tracks time flawlessly while missing the cycles entirely.

In contrast, other great kincentric civilizations did not “solve” the discrepancy between solar orbit, spin and lunar cycles (not to mention other planetary and galactic cycles).

They honoured and centred their societies upon them.

These cyclocentric societies allowed time to overflow its containers. They recognized intercalary periods as thresholds rather than errors. And upon this living foundation, they built cultures that accumulated ecological insight cycle by cycle—each return deepening awareness, strengthening reciprocity, and reinforcing harmony.

For much of history, the ecological consequences of abandoning this orientation were muted by scale. The Roman world, for all its temporal rigidity, remained small compared to planetary systems.

Today, it does not.

After two millennia of compounding linearity, humanity now finds itself pressing against biospheric limits. The mechanization of time has marched in lockstep with the mechanization of life. Disconnection from cycles has become disconnection from consequence.

What we are experiencing is not merely ecological crisis.

It is first and foremost temporal dissonance.

It is time to rethink time. There's no other way to changes our times.

Footnotes

_________________________________________________

1. There are some notable historical initiatives: In the mid-1950s, proponents of a new World Calendar, brought their proposal of a perennial year to the UN. Various governments were in favor until the US to rejected the motion to take it further. In the early 2000's Jose Argueles tried to implement the 13 Moon Calendar arguing that nothing was more important: "A crooked measure produces crooked judgments. A crooked calendar produces crooked lives."

- For an an account of the Igorots remarkable ecological synchrony with the cycles of the living world around them see: William Henry Scott, (1959), American Anthropologist 60(3):563 - 570, Some Calendars of Northern Luzon

- There is, in fact, another cycle at work here. Earth’s axis undergoes a slow wobble on its axis. This wobble, which is separate from Earth's orbit, makes a full circular wobble approximately once every 25,772 years. This "axial precession" causes the seasonal markers—such as solstices—to arrive slightly before Earth completes a full orbital return relative to the stars. As a result, the time between successive solstices (the tropical year) differs from the time it takes Earth to return to the same orbital position in space (the sidereal year). The mean tropical year is approximately 365.24219 days, while the sidereal year is approximately 365.25636 days, or 20 minutes and 24 seconds and corresponds to an axial shift of roughly 50.3 arcseconds 0.014° per year. As yet another Earthen cycle, we will return to the significance of this, in the next essay. 🙂