The Salmon's Spiral

The Earth’s cycles tend towards the outwards dissipation of energy. —Earthen Ethic No. 2

Twelve thousand years ago, as trillion ton ice sheets retreated leaving nothing but rocks and rivers, the salmon found their niche on North America's Pacific coast. There, hundreds of kilometers inland, they began a seasonal cycle that has spun to this day. Every year, come the thaw of winter ice, tiny hatch-lings emerge from batches of eggs hidden on the bottom of streams and creeks. Over the spring, the tiny fish gather their strength, consuming insects and waterborne larvae. Come summer, they set out on a journey downriver to the Pacific. Once arrived, they feast on nutrient rich marine life, steadily gathering fats and amassing proteins. After several years, having reached their full size and strength they are ready to head home. In autumn, as they retrace their original river route, the waters boil with their determination– and an entire ecosystem revels in their return! Bears, eagles and humans gather for grand fishing feasts. Even the bugs partake! Discarded carcasses nourish the very insects upon which the salmon first fed. Meanwhile, those salmon that slip by continue to the waters where their lives began. There, they use the last of their strength to deposit batches of roe and cover them with gravel. With their eggs safe, the salmon die; their decomposing bodies a final nutrient-rich gift to the river ecosystem that their roe will soon run.

OVER THE LAST MILLENNIA, the Pacific Salmon have played a key role in regenerating the barren desolation left by the glaciers that once covered America's Pacific Coast. Year after year, their cycles have relentlessly spun, inexorably distributing nutrients up and down the coastal interior. Today, the continent's coast is a thriving biome of tens of thousands of species. The vast and verdant transformation is a reminder to us humans of our own regenerative potential.

As we saw in our chapter Nature's Fallacy, contrary to long held misconception, humans are not separate from 'nature'— rather, we are subset systems of the biosphere— and by extension, so too are our enterprises and economies. In this way, the masterful management of energy and matter by our Earthen kin, can provide us not just insight, but inspiration. Indeed, as we strive to ensure that our modern enterprises are green we have much to learn from the ways of the salmon— in particular, the way in which they manage their energy to enrich both themselves and the ecosystems of which they were a part. As we will see, the Salmon’s inward spiral of energy emulates the vortical pattern by which the Earth has greened the biosphere. This pattern, which has long under-laid the ethics, traditions and language of kincentric cultures, provides the geometry for our second Earthen ethic. With its help, we can make sense of the depletion wrought by the purposes for which our modern enterprises operate— and discern the requisite energetic structure for our enterprises that are keen to be green.

Just as we move on from our old view of humans as separate and exceptional to the biosphere, so too must we move on from a similar view of our enterprises. With an understanding of the inextricable immersion of our economies within the Earth’s systems, we can see the capital and currency that energize our enterprises from a fresh, planetary perspective.

Just like organisms and ecosystems, our enterprises and economies are energy systems that circulate the transmuted energy of the sun. As each circulate energy, all operate as subset systems of the biosphere and share important parallels.1 Whereas an organism manages energy in the form of proteins, fats and carbohydrates, an enterprise manages assets, capital and currency. Whereas an organism manages its give and take of nutrients over seasonal cycles, an enterprises manages its revenues and expenses over fiscal cycles. Whether organism or enterprise, as their processes spin, their particular give and take of energy creates a pattern all their own— especially in the inclination of their cycles.

As we saw in our last chapter, cyclic repetitions always incline in one direction or another, spiraling inward or outward; tending towards either depletion or enrichment. In order to emulate the enriching inclinations of organisms like the salmon, our enterprises must embody the same cyclical pattern— a spiral geometry that is rooted in the cosmological character of the Earth.

To understand the underlying Earthen pattern of energy management, we must return once again to our planet's primordial origins.

Over the last four billion years of our planet's unfolding, the energy of the Sun's relentless blaze coursed through the Earth's cycles of geology, ocean and atmosphere. Driven by the rigid dictates of thermodynamics and guided by Earth's unique cosmological character, cycles unfurled that ever better dissipated the Sun's energy. Configurations of matter organically emerged that gathered, converted, stored, then dispersed energy ever outwards towards equilibrium.2

Soon the sun’s shine was being stored in complex, energy-dense molecules such as fats, proteins and carbohydrates that were interchangeable among cellular systems. As one organism lived and died, it was consumed by others and the energy embodied within its nutrients was passed on. As organisms gained the energy of those before them, they reproduced and proliferated. In this way, each cycle of life steadily spun its nutrient energy outwards to other organisms all across the planet’s surface.

With countless life cycles spinning, collectives of organisms became systems unto themselves. These systems of systems then spun their energy upwards again. From organism to ecosystem, from ecosystem to biome, energy was spiraled ever outwards towards the enrichment of all.

And the biosphere blossomed.

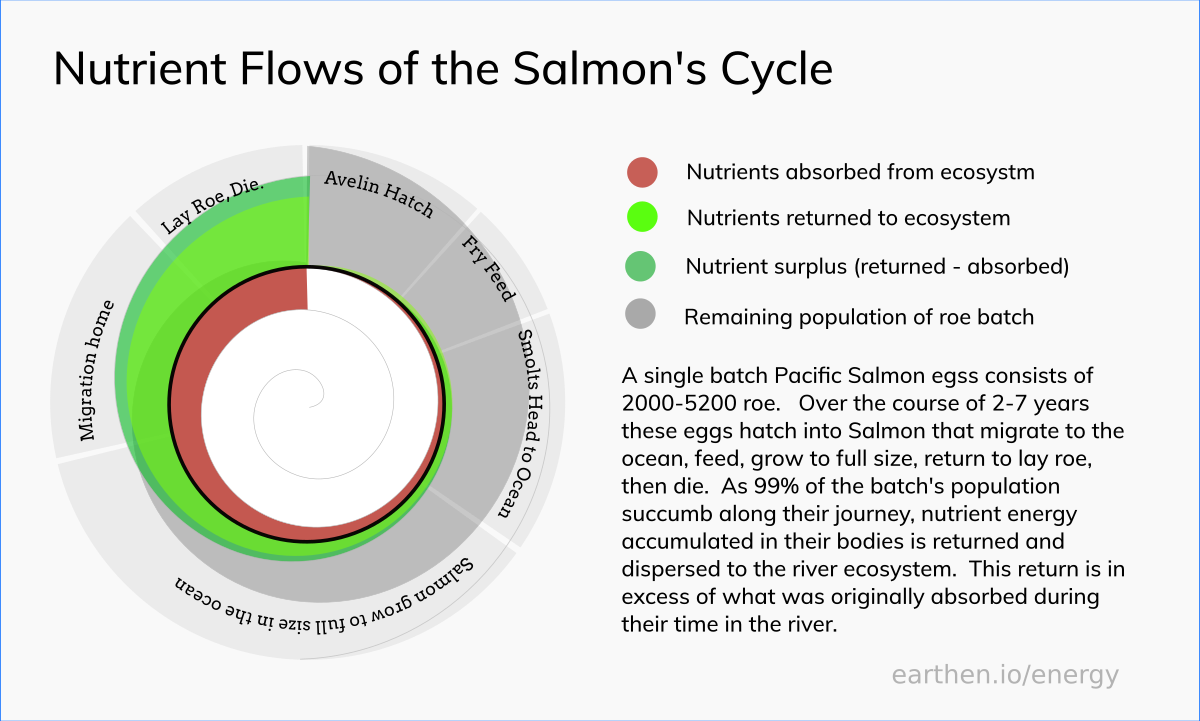

Looking closely at the life cycle of the salmon, we can see that their pattern is a magnificent reflection of the Earth’s.

Just as the Earth’s accumulation of solar energy powers its planetary processes, the salmon’s steady accumulation of nutrient energy powers its life process. As it eats, nutrient energy is gathered and converted into the fish's fats and proteins while carbohydrates power its swim. Then, just as the cycles of the Earth disperse energy out to all, as the salmon are preyed upon and consumed, their accumulated nutrients are spun outwards to their ecosystem.

In the end, a batch of Salmon distribute far more nutrients out to their ecosystem than they keep for themselves. In fact, this ratio of distribution is precisely what makes the salmon so exceptional. From a single batch of 2000 to 5200 eggs the resulting salmon can accumulate a biomass of several tons. Yet at the end of their cycle only 20-50 salmon return to spawn, leaving only several kilograms of eggs for next cycle to begin.4

Not only does this contribute to a common home for many creatures to thrive, the spiral continually optimizes the conditions for their own subsequent generations. In this way, the salmon proliferated in rivers up and down the North Pacific coast, contributing to the enrichment of rivers, forests and human cultures over the last twelve thousand years.5

Today, as we focus our efforts on reducing the ecological harm of our modern enterprises, we often forget that we too are organisms capable of contribution.

As we saw earlier, we humans have not only lived on America’s Pacific Northwest Coast since the last ice age, we too played a key role in the ecological enrichment of the continent.

Nations such as the Haida, Dakelh, and the Wetʼsuwetʼen, among many others, are renowned for the ecological vitality of the lands they have long presided over. They have lived side by side the salmon for countless generations– and learned from them. Seeing the salmon as ecological elders, they wove the salmon's dispersion lessons into the stories, morals and languages of their culture.

In Haida stories, the Salmon were seen as a type of people. They taught important lessons about respecting one another. In particular, that the bones of the Salmon were always to be dispersed back to the rivers just as the Salmon’s bodies were to be dispersed among the community.

In Wetʼsuwetʼen culture, this ethic of dispersion was codified in tradition. The first Salmon caught of the season would be shared with every member of the community, meticulously ensuring that every morsel was consumed and each bone returned to the water.

In the Dakelh culture, dispersion was embodied in their Carrier language. Grammatically, it is impossible to speak of 'my salmon' only of 'our salmon'.6

For the Haida, Dakelh, and the Wetʼsuwetʼen an ethic of take only what is needed, and distribute what is taken underlaid their ways of life– making no distinction between economy and ecology. Just as we saw in the Igorot Ayyew ethos, honor and respect were gained not by wealth itself, but by its flow; not by how much was gathered, but by how much was given back to both people and the land.

In the deep resonance in the distributive ways of the Igorots, Haida, Wetʼsuwetʼen, Dakelh, the Salmon and the Earth, we find our second Earth ethic.

Just as the Earth tended its cycles towards the spin of energy outwards to the benefit of all, so too must we intend and achieve with our own. Only when the intention and the result of our cyclical processes is the net-outwards distribution of energy, is this Earthen ethic met. Only then can our enterprises be considered an ecological contribution— and green.

As we strive to ensure our modern enterprises are green, the second Earthen ethic shows us that their pattern of energy is key.

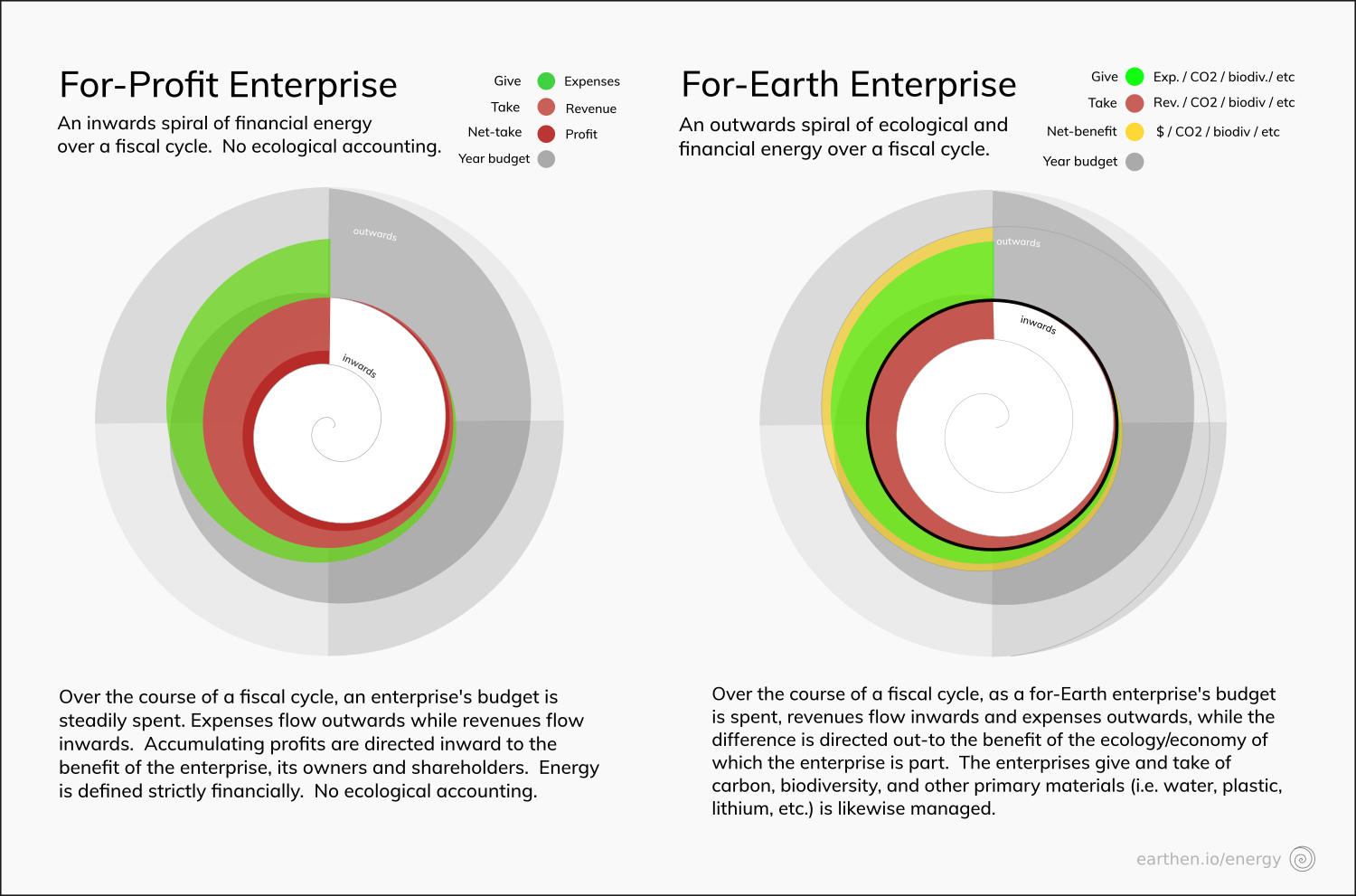

When it comes to our enterprises, their pattern of energy management is determined by the purpose for which the enterprise is established. The for-what of an enterprise determines how and why it receives revenues and expends expenses— as well as the how and why of its ecological give and take.

While most enterprises operate with the purpose of meeting human wants and needs— such as for the provision of products and for the delivery of services— often modern enterprises are structured for a deeper reason.

Certain enterprises are established by their owners for the purpose of profit: generating more energy than they give back. This excess energy, although often sourced ecologically, is defined strictly in financial terms. While these for-profit enterprises may provide products, services and even ecological benefits, their structure dictates that their financial surpluses are directed to their owners (or shareholders as the case may be) at the end of each financial cycle. The result is a process of accumulation that over many financial cycles, steadily depletes the ecological and social systems of which it is part.

In this way, the energetic inclination of a for-profit enterprise, spins in opposition to the pattern of the Earth. No matter how green-intentioned, no matter how green its short-term impacts may seem, its management of energy is the very opposite of ecological contribution.

Of course, not all modern enterprises operate for-profit.

Today, more and more enterprises are aware of the depleting dynamic of profit in-and-of-itself. In order to contribute to their social and ecological environment, many enterprises choose a ‘not-for-profit’ energetic structure. These enterprises strive to return all their revenues back to the pursuit of their social or ecological purpose.

However, insofar as a not-for-profit enterprise remains fully immersed within the paradigm of profit— where energy is accounted for strictly as revenues and expenses— their energetic structure is insufficient to be green.

While an enterprise may ensure that all its revenues go out to its social or ecological purpose, insofar as its energy is accounted for solely in financial terms, it will fail to account for its ecological give and take. In particular: its give and take of carbon, its support or depletion of biodiversity and its raising or lowering of awareness (our next three Earthen ethics). In this way, a not-for-profit enterprise may return all of its financial energy back to its purpose, yet still be complicit in the systematic depletion of the ecosystems, biomes and the biosphere of which it is part.

In other words, without both not-for-profit and net-green intentions— and an accounting of both— an enterprise cannot be green.

While in the short-term, an enterprise may sequester much carbon, plant many trees and support many species; without an accounting thereof, one cannot be certain, whether these impacts are in fact a net-contribution. It could well be that more carbon is emitted, more trees are cut, and more species are depleted to achieve these results!

However, the path to net-green has never been clearer.

Just as a shoal of salmon direct all their energy towards their out-to-all journey home, our green-intentioned enterprises must direct all their energy towards an out-to-all-purpose.

Learning from kincentric cultures, such a purpose must embrace both the social and the ecological, recognizing that both, from the perspective of the Earth, are one and the same. This dual not-for-profit and net-green intention, must be declared and accounted for— ensuring that all the enterprises revenues go towards this for-Earth purpose and that all the other Earthen ethics are fully met.

That said, the outwards spiral of energy is only half of the Earth's spiral pattern of enrichment.

There is yet the matter... of our matter.

Our next Earthen ethic.

A decade ago, Banayan Angway and Russell Maier; an Igorot wisdom keeper and a western philosopher, joined forces to protect the Chico River in the remote Northern Philippines from an inundation of plastic pollution. As the plastic transition movement they started has spread throughout the world, they continued to explore the modern relevance of indigenous ecological wisdom. Guided by the Igorot Ayyew eco-ethos, they are publishing a systematic theory of green and grey in the form of a philosophical treatise. The Full Story of the Tractatus Ayyew

Footnotes

Sources on the Salmon's distribution of marine nutrients on the Pacific Coast of North America:

Quinn TP, Helfield JM, Austin CS, Hovel RA, Bunn AG. A multidecade experiment shows that fertilization by salmon carcasses enhanced tree growth in the riparian zone. Ecology. 2018 Nov;99(11):2433-2441. doi: 10.1002/ecy.2453. Epub 2018 Oct 23. PMID: 30351500.

Hilderbrand GV, Hanley TA, Robbins CT, Schwartz CC. Role of brown bears (Ursus arctos) in the flow of marine nitrogen into a terrestrial ecosystem. Oecologia. 1999 Dec;121(4):546-550. doi: 10.1007/s004420050961. PMID: 28308364.

Hilderbrand GV, Hanley TA, Robbins CT, Schwartz CC. Role of brown bears (Ursus arctos) in the flow of marine nitrogen into a terrestrial ecosystem. Oecologia. 1999 Dec;121(4):546-550. doi: 10.1007/s004420050961. PMID: 28308364.

1. Suh, Sangwon. (2004). Materials and energy flows in industry and ecosystem networks. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 9. 335-336. 10.1007/BF02979425. Materials and energy flow analysis (MEFA) has been widely utilized in ecology and economics, occupying an important position in both disciplines.

2. Guillaume Gauthier et al, (2019) Giant vortex clusters in a two-dimensional quantum fluid, Science https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aat5718

3. The growth of salmon https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Growth-performance-average-salmon-weight-from-fry-stage-to-market-size-for-the-three_fig4_303095240

4. Thomas P. Quinn, The Behavior and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout (2018)

5. Nigel Hagan, (2006) 12,000+ Years of Change: Linking traditional and modern ecosystem science in the Pacific Northwest, UBC Fisheries Centre, p4 “In the last 13,000 years, many thousands of stocks of Pacific salmon and sea-run cutthroat trout colonized the lakes, rivers and streams.”

6. The author's own experience learning the carrier language.

7. For the Wet’suwet’en the example of the salmon was impossible to overlook. Among the multitude of creatures around them, the extremes of life and death were never so dramatic. Over years of feeding in the ocean, the Salmon achieved the pinnacle of ecological vitality; massive and magnificent creatures writhing the waters with strength and vitality, making the rivers boil with their numbers and strength. In incredible feats of stamina and endurance they swim rapids and leap waterfalls to return home.

8. “For the Gitksan and Wet'suwet'en, as for other traditional peoples, the various beliefs about the relationship of humans to the land and to the resources which sustain the people are rich and multifaceted, integrated into all aspects of society. They do not have a reductionist perspective which allows separation of the biological from the moral or mythical. Adherence to a wide variety of practices which we might separate into "biological" and "spiritual" realms is seen as necessary for the maintenance of the relationship of the people and the land with its plants and animals which sustain human life. Conservation is interactive with ideology. As Anderson points out, it is in the realm of ideology and myth, which entrain the emotions, that the motivation to defer present gratification for the future common good is obtained. Myths or teaching stories imbue lessons on conservation, which makes possible long term sustainable adaptation, with sufficient emotional loading to make them memorable and to inspire people to put the lessons contained in them into practice.” Leslie M. Johnson Gottesfeld (1994), Conservation, Territory, and Traditional Beliefs: An Analysis of Gitksan and Wet'suwet'en Subsistence, Northwest British Columbia, Canada. Human Ecology, p20.

9. Nigel hagan,(capital H) (2006) 12,000+ Years of Change: Linking traditional and modern ecosystem science in the Pacific Northwest, UBC Fisheries Centre, p4 “In the last 13,000 years, many thousands of stocks of Pacific salmon and sea-run cutthroat trout colonized the lakes, rivers and streams.”

10. Hinton and McCluran, in their book present a compelling argument of the extractive nature of for-profit business. They propose this ethic of generative determination: “...in order to determine whether business is generative (contributing to the health of the whole economy) or extractive (taking away from the health of the whole economy), one must ask the question, “Who profits from the profit?”” Jennifer Hinton, Donnie Maclurcan, (2016) How on Earth, Post Growth Institute.